Australia has one of the highest rates of spending per child on toys, with our children averaging 250 toys each. Today’s consumer society and marketing drives parents to buy more toys, whether it be buying the latest trend, responding to a child’s demand for what they’ve seen advertised on TV, or being guilted into getting ‘educational’ toys so their children don’t ‘fall behind’.

However, studies now show something Montessori observed and made key to her education approach – children with fewer toys have better quality play and learning. Studies show that scarcity rather than abundance sparks creativity, encourages imagination, develops longer attention spans and improves social skills.

In various studies*, children exposed to a higher number of toys in an environment engaged with them with less depth and duration – their focus was less, and they gained less benefit. With fewer toys they were able to use imagination in their playing, inventing and expanding play. Children with fewer toys also were able to develop their interpersonal relationships with other children and the adults, being more present rather than bouncing from one unsatisfying experience after another.

We sometimes hear the question as to why current scientific studies into children validate Montessori’s philosophy that was developed over 100 years ago. The answer is that Montessori herself engaged in scientific practice, studying childhood development, researching what worked and what didn’t, and creating programmes to optimise the natural development of the child.

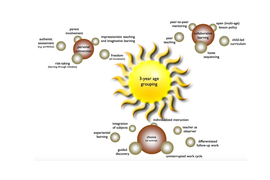

Many may have heard how she started with a group of children, introducing an abundance of toys, then observing what the children were drawn to and what they weren’t. She constantly changed the environment, removing what didn’t work, focusing on what did. Key was her observation that nothing goes into the mind that does not first go through the hands. She saw that the children were drawn to ‘real’ work, and so included practical life materials for the classroom, which can be mirrored in the home environment. Real, everyday tools of children’s size to encourage sweeping, pouring, washing, dressing, etc. The practical life materials invite the child to develop and refine their movements, develop their concentration by introducing activities with increasingly complex steps, to work at their own pace uninterrupted, and to complete a cycle of work which typically results in the feelings of satisfaction and confidence.

Parents are encouraged to share these practical life activities with their children in the home environment as part of their ‘play’. Indeed, Montessorians don’t use the term ‘toys’ for these materials. The activities are the child’s work: as Montessori shared “small children have a tendency to work at their play, imitating the actions of the adults. They don’t consider what they do to be play – it is their work”.

* Missing, R., 1996. Der Spielzeugfreie Kindergarten. 1st ed. Germany: Don Bosco Verlag.

Phlipot, M.L., 2014. Does the Number of Toys in the Environment Influence Play in Toddlers?. Occupational Therapy Doctoral Program. Department of Rehabilitation Sciences: The University of Toledo.